I never thought I’d go back to Puerto Peñasco.

I visited the first time in 1971 when it was small town of about 7,000 along side a Tohono O’Odham village. I camped on the outskirts and never even saw the town. I returned in 1985 when it had swelled to 10,000—one comfortable hotel and a few restaurants. I loved it.

In 1993, I was horrified by the population explosion. There must have been 25 or 26,000 people there. I told my then-husband it was ruined and I’d never return.

But when my friend Frank was house sitting there and got permission for me to come visit, well … well, it was Mexico after all. Even with a winter-time population nearing 80,000, it would be nice to see Frank and I figured I’d enjoy the sea and food.

So I went, deciding ahead I’d have to pretend it was someplace I’d never been. And because it was completely unrecognizable, in a sense that was true. I’d never been to this Puerto Peñasco before.

Let me tell you who Frank is. We met about six years ago when he was couchsurfing his way across the southern US, headed back to his home near Seattle. He found my offer of a place to stay via the website, couchsurfing.com. It was free then, but today it’s a subscription site, though affordable. If you want to travel affordably, sign up—it’s great!

Frank has been leaving the cold, rainy northwest for Arizona sunshine every winter since and has stayed with me many time. This time, I’d be visiting him.

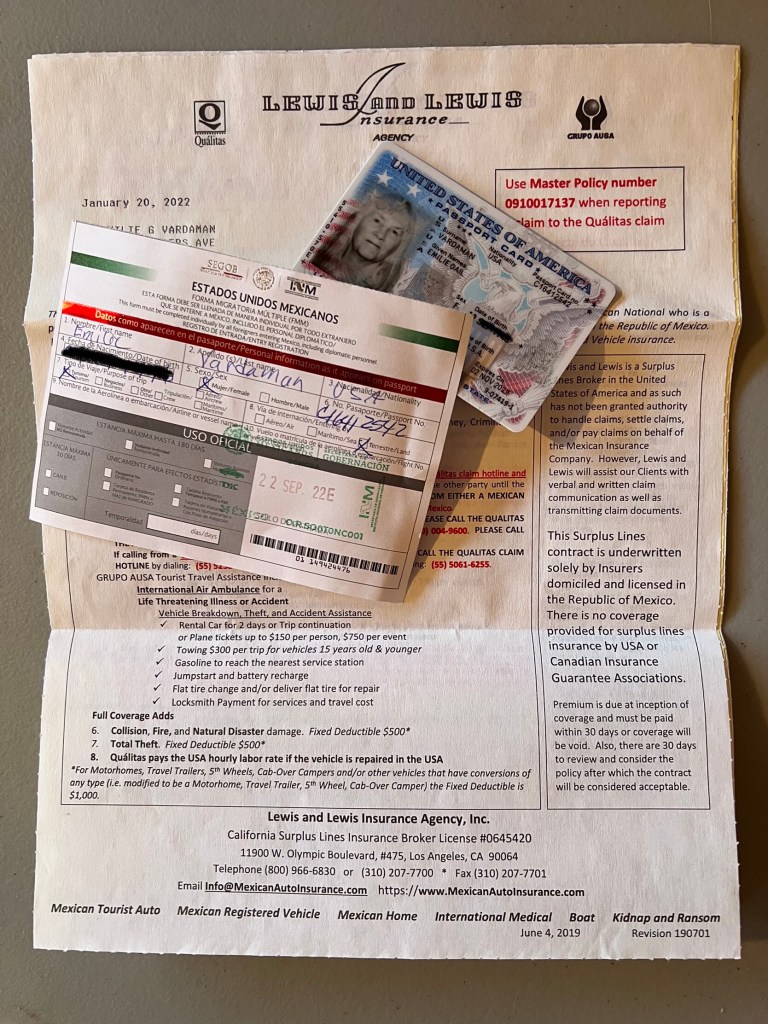

I crossed the US/Mexico border before 8:00 am and arrived in Cholla Bay (also Choya Bay, the gringo spelling) before 10. Frank helped me get my things inside, showed me the rooftop deck, and we immediately went out for a late breakfast.

Great huevos rancheros at Xochitl’s Cafe though the salsa was gringo-ized and not very spicy.

In the ten days I was there, Frank and I sampled a lot of restaurants, saw daily sunrises and sunsets, visited bakeries, and toured around a bit. All this in addition to shopping for groceries, wandering the malecón, and lounging on the roof.

One day we visited El Barco, the women’s oyster co-op. El Barco is the only female owned and operated oyster farm in Puerto Peñasco, and they also have a restaurant with a view.

We roamed CEDO, the Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans, where we saw the skeleton of a fin whale. The bones were found in the area in 1983 and were eventually moved and reassembled at the CEDO site.

We visited two bakeries, my favorite La Tapatía, where breads and rolls were still baked the old fashioned way.

Frank took me to the malecón and I went back once on my own. A malecón similar to a boardwalk in that it fronts the ocean or sea. It’s often made of stone. It or the area around it usually has stalls with vendors selling food, local handicrafts and arts, tickets to boat rides, blankets, clothing, and more.

There are lots of boats in Puerto Peñasco.

I was fortunate to be in town for Día de los Muertos, Day of the Dead. Vendors sell marigolds for people to place on the graves of their loved ones. The belief is marigolds attract the souls of the departed, so graves are decorated with them as are altars created specially for the holiday.

One area of town had a display of altars.

Catrinas were everywhere. Catrinas are skeleton dolls, artwork, and even sculptures representing the dead for Día de los Muertos.

CATRINA

Each morning, sunrise lured me to the rooftop.

Most days ended with sunset on the beach.

My ten days in Puerto Peñasco showed me it’s not good to write off a place because it isn’t the way it used to be. Peñasco is a vibrant small city. I’d found it wonderful in 1971 and 1975. If I hadn’t felt so irritated by its growth, I’d have seen it was probably wonderful also in 1993. I sure thought it was on this visit.